| Home . Formation . Equipment . Funding . Local Agreements . Captains . 1897-1933 . Joint Brigade . WW2 . Post War . 1950s . Fires . Gallery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Second

World War

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This

chapter does not deal exclusively with the activities of Broadway’s

fire brigade during the Second World War, but includes the work of other

civil defence branches where relevant.

The

poor state of the fire service in this district in the late 1930s was

reflected throughout Britain's rural areas. For the most part fire brigades

were run by parish, district or town councils, often using out dated

equipment. Neighbouring brigades frequently had different types of hose

and hydrant couplings. So, even if they had mutual assistance agreements,

their equipment was not always compatible.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

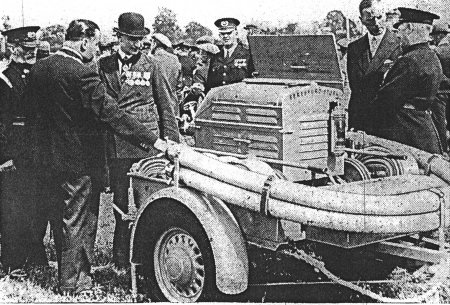

A Home Office trailer pump on show at the Civil Defence rally in Evesham in July 1939 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

With

the political situation worsening in Europe, the British Government

took action to improve the country's fire fighting capability. The outcome

was the 1938 Fire Brigades Act which received Royal Assent on July 28th

1938, and resulted in the setting up of 1440 separate fire authorities

in England and Wales, and 228 in Scotland. The Act made Borough, Urban

and Rural District Councils responsible for fire protection, and required

them to provide means of fire extinction, either by having a properly

trained fire brigade or by entering into an agreement with a neighbouring

council. It also gave the Secretary of State the power to appoint inspectors

who could prescribe standards of efficiency, and intervene if, two years

after the passing of the Act, any local authority had not provided an

effective service. The 1938 Act marked the end of parish brigades, as

it was now illegal for parish councils to raise money for fire fighting.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The

Act did not effect the running of the Broadway brigade as it was already

under Rural District Council control, and had been since 1933. (The

1938 Act caused a problem for Broadway Parish Council, with regard to

ownership of the fire station, which did not become apparent until about

fourteen years later. This is discussed in a later chapter).

Under the 1938 Act, fire authorities were required to enter into mutual assistance agreements with their neighbouring brigades. Until the passing of the Act there had been no statutory obligation for local authorities to provide fire cover, a fact that, when they heard it, surprised and amazed some members of the House of Commons. An interesting provision of the 1938 Act was that, from two years after its passing, no fire authority would be able to require owners or occupiers of property where fire occurred to make any payment. Every person was, for the first time, able to receive the services of a fire brigade without charge. These were undoubted improvements on previous arrangements but, with the benefit of hindsight, the 1938 Act was, later, described as being years behind even peace time requirements. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

During

the summer of 1939, war with Germany seemed inevitable, and in this

district, as in others, considerable concern was being expressed about

our lack of preparedness. Evesham Rural District Council, at their meeting

in June of that year, strongly endorsed a resolution passed at a gathering

of the rural district's Head Air Raid Wardens. The wardens were protesting

about the lack of civil defence in the rural area. They drew particular

attention to the totally inadequate fire fighting facilities, which

in many places were insufficient for peace time, let alone the imminent

war. They pointed out that the fire engine stationed at Pershore (they

were, understandably, discounting Broadway’s forty year old manual

engine) had to cover an area extending from the Worcester city boundary

to Broadway Hill, and from Inkberrow to Overbury, an area of about one

hundred and fifty square miles. While, on the other hand, the borough

of Evesham had an engine all to itself. This unacceptable and, frankly,

dangerous situation had arisen due to, as described in a previous chapter,

the inability of the neighbouring Councils to co-operate with each other.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The

public's perception of fire fighting as still being a community affair

was demonstrated in the first month of the war. In some villages, Offenham

and Cleeve Prior amongst them, money was raised by local residents in

order to set up volunteer brigades. Following the 1938 Fire Brigade

Act parish councils were not allowed to raise money for fire fighting.

But Evesham Rural District Council did offer the services of the Joint

Fire Brigade Committee to give practical help to villages trying to

provide fire fighting facilities by public subscription. Given the perceived

threat, and poor state of the district brigades, it was no surprise

that people were driven to make their own fire fighting arrangements.

From then on, steady improvements were made to the village brigades. A trailer pump, to replace Broadway's forty-two year old manual pump, had been delivered, and was in service, by the Autumn of 1939. To meet Home Office standards, two more pumps were required in the area; one for the Beckford district, and one for The Lenches. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Much

attention was given to training. Large scale exercises were carried

out involving all branches of the civil defence from Evesham and the

rural district. On the morning of Sunday 22nd October 1939 one such

exercise took place with imaginary bombs falling on Willmot's factory

in Evesham, and a high explosive bomb detonating in front of The Lygon

Arms hotel in Broadway, causing four ‘casualties’. A further

unexploded bomb was found at the rear of The Lygon Arms. Other exercises

involved just the Broadway civil defence branches. In February 1941

a demonstration of fighting fires caused by enemy action, to which the

public were invited, took place on the Village Green. The use of stirrup

pumps and sand to extinguish incendiary bombs was demonstrated by the

fire brigade. Later that year another joint exercise was carried out

in Broadway with a decontamination squad operating in Orchard Avenue,

and the fire brigade working at the rear of the hunt kennels.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Broadway Home Guard |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Major

Tristram, Broadway's head warden, used this occasion to appeal for volunteers

to come forward as stretcher bearers, and for people with first aid

experience to work as ambulance and sitting car drivers. People were

also urgently needed to act as fire watchers during the hours of darkness.

Any fire could attract the attention of enemy aircraft which were ever

present over Britain at this time. Unfortunately, Major Tristram’s

appeals for volunteers were largely ignored by the villagers, and a

month later at a public meeting of the Parish Council he was driven

to make a scathing attack on the apathy of the local population. Major

Tristram said, "The response to the appeal for fire watchers

had been very poor". He added, "It is about time the

general public of Broadway woke up to the fact that there is a war on.."

Another speaker, Mr A Turner, an evacuee from London joined the condemnation, "There are hundreds of people in Broadway who are absolutely hiding away from the war ". Major Tristram went on to say that despite the best efforts of himself and his wardens to enrol fire watchers, the residents of Broadway had failed to respond. However, he paid tribute to the Boy Scouts, who, entirely on their own initiative, were patrolling the village from 9pm until midnight! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The armband worn by fire watchers |

This

apparent indifference is difficult to understand, as only a few months

had passed since German aircraft had dropped incendiary bombs onto the

village, causing a major fire. Many, of course, were only too well aware

there was a war on. They had family members in the forces and, even

at this early stage of the war, at least one villager had been lost

in action. Fortunately, it seems that Major Tristram's outburst did

stir the consciences of some in the population, because he was able

to report two weeks later, in April 1941 that, "People are falling

over themselves to join the band of fire watchers". Later that

year the voluntary fire watchers became known as Fire Guards, and were

issued with identity cards authorising them to enter properties where

they suspected fire. It was at about this time that the Air Raid Precautions

Services (A.R.P.) became known as the Civil Defence

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Despite

having bombs dropped on the village, the residents never had the benefit

of an air raid warning siren. Although there appeared to be good reason

for not having a siren, the arguments, for and against, were the cause

of much heated debate in the village throughout the war. For a detailed

account read The

Siren Saga.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As

the war progressed additional fire fighting equipment was supplied to

Broadway’s Civil Defence service. Stirrup pumps were issued to

some villagers, and by late 1940, Major Tristram reported that he knew

the location of thirty-five. These pumps, when operated by two people,

provided quite an effective fire fighting jet from a bucket; delivering

about two gallons of water per minute. It was suggested properties where

pumps were located should display a sign outside with the letter "P".

Concrete stanks (dams) were built across the brook which runs at the bottom of the recreation ground, to provide fire fighting reservoirs. There was another near the bridge in Cheltenham Road. Later, several rectangular steel tanks, each of which held five thousand gallons of water, were erected in the village. One was positioned at the entrance to Springfield Lane, and another in Orchard Avenue at its junction with Wells Gardens. Two large tanks were built on the flat roof of the kilns at Gordon Russell's factory. They were joined by a levelling pipe, and a female instantaneous coupling was fitted for the direct connection of a fire hose |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The remains of one of the wartime stanks near the recreation ground in Broadway. Photographed in 1996 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Following

German air raids on Britain in 1940, it became clear that fire fighting

efforts needed to be co-ordinated nationally. By an Act of Parliament,

which came into force on 18th August 1941, the 1600 fire brigades in

Britain were formed into the National Fire Service (NFS).

The Broadway brigade became part of Area No.23, the Headquarters of which was Bevere Manor near Worcester. The firemen were issued with N.F.S. uniforms and steel helmets. Broadway's firemen were on call from their work or homes during the day and, later in the war, took turns to sleep at Steward's builders yard where the trailer pump was stationed. Charles Steward’s premises was a far better base for the fire brigade than the fire station. His lorry, which was used for towing the pump, was there, a telephone was available to receive calls, and there was accommodation for the men to sleep. None of which was available at the fire station. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Training

sessions were held at Evesham on some evenings and some Sunday mornings,

with instructional films occasionally being shown at the cinema. One

training film, "U.X.B." was shown to a large company of

fire brigade and civil defence personnel at The Clifton cinema one

Sunday morning. The film, dealing with the identification of German

bombs, was shown following a lecture given by a bomb disposal officer.

Often on the return journey to Broadway, following lectures or films,

a detour was by made by the crew via The Wheatsheaf public house,

at Badsey. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There

were several large fires in Broadway during the war. On the night of

December 11th 1940 a German bomber dropped a quantity of incendiary

bombs on the village. A number of them fell on Gordon Russell's furniture

factory setting light to a large wooden, thatched barn. The building

containing fine furniture and textiles, brought from London for safe

keeping, was quickly destroyed. Ironically, the barn also contained

a large order of furniture for Sir John Anderson - the Minister for

Air Raid Precautions!

Another incendiary landed on the machine shop roof burning a hole, before being extinguished, it is believed, by a factory worker who lived nearby. The temporary plywood patch which was nailed on the underside of the hole was still in place when the factory was demolished in 2004. When a cottage adjacent to the factory was recently re-thatched, an unexploded incendiary bomb was discovered lodged in the old thatch. According to an Evesham Journal report, published at the end of the war, bombs fell in the Broadway area on seven separate occasions. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A

fire, of unknown origin, at the North Cotswold Hunt stables, on the

night of 17th January 1941, caused considerable damage. The Broadway

brigade with Charles Steward in charge was in attendance, as was the

district brigade from Pershore. Following this incident there was some

criticism regarding the time it had taken for the brigade to arrive,

and the delay in putting water on the fire. The delay was mainly due

to the firemen having to be fetched from their homes, there being, at

that time, no call out system. It was not until later in the war that

the crew began to sleep at Steward's yard where, as mentioned previously,

the fire pump was stationed, and where a telephone was available. A

second fire in May of that year occurred only yards away from the one

at the hunt stables. A garage belonging to the butcher, H.H.Collins,

was severely damaged by fire. Two vans were removed undamaged, but a

car was destroyed. The Broadway brigade was on the scene in under twenty

minutes, and set their pump into one of the recently constructed stanks

in the nearby brook.

On

26th May 1943, at about 10.30am, the Broadway brigade was called to

an aircraft crash at Collin Lane, Willersey. A Whitley bomber, LA

845, shortly after taking off from Honeybourne, had suffered engine

failure and came down, killing the pilot and seriously injuring the

rest of the crew.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A

large thatched house in Springfield Lane, the residence of Major C.M.

Napier, was almost completely destroyed by fire in 1943. At about 9.15pm,

on 3rd March, Major Napier noticed the chimney was on fire. The alarm

was raised, and the Broadway brigade under Charles Steward was quickly

on the scene, followed later by units from other stations. The fire

was soon out of control and, it was said, could be seen from twenty

miles away.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Following

this incident the efficiency of the fire brigade was once again questioned.

The main complaints, made by the Parish Council, were of faulty hose,

poorly trained firemen, the fact it took twenty minutes to start an

engine (possibly the trailer pump), and the considerable time taken

to get water from the static tank. National Fire Service representatives

answered the complaints at a meeting with the Chairman of the Rural

District Council. The N.F.S. officers said some delay was caused because

supporting units were not given the precise location of the fire, so

had difficulty finding their way. He recommended that, in future, someone

be delegated to meet the supporting units in order to give them accurate

directions. In defence of the Broadway crew, it must be said that they

would have been faced with a considerable problem obtaining water to

put on to the fire. The water main in Springfield Lane was for domestic

use only, and not large enough for fire fighting. So they would have

had to set their pump into either the static tank or the water main,

both situated in High Street, a distance of about six hundred yards.

Burning thatch is, even with modern equipment, difficult to extinguish,

so given the poor water supply it is not surprising the building was

lost.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NFS Cap Badge |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By

the Autumn of 1944 an allied victory in Europe seemed certain and, nationally,

various sections of the Civil Defence began to stand down. Britain's

largest ever unpaid army, The Home Guard, was stood down on November

1st 1944. There were some who were sorry they were disbanded before

the end of the war with Germany. As one Home Guard officer stated in

a speech given at a dinner in Evesham, ‘For some there is an

illogical disappointment that they had no opportunity of coming to grips

with the enemy.’ The Fire Guard (the fire watchers) was officially

disbanded at the end of 1944. Broadway Parish Council sent a letter

to Major Tristram, Broadway’s head warden, thanking him for his

work, and for that of his wardens. They also thanked the National Fire

Service which, of course, remained operational.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||